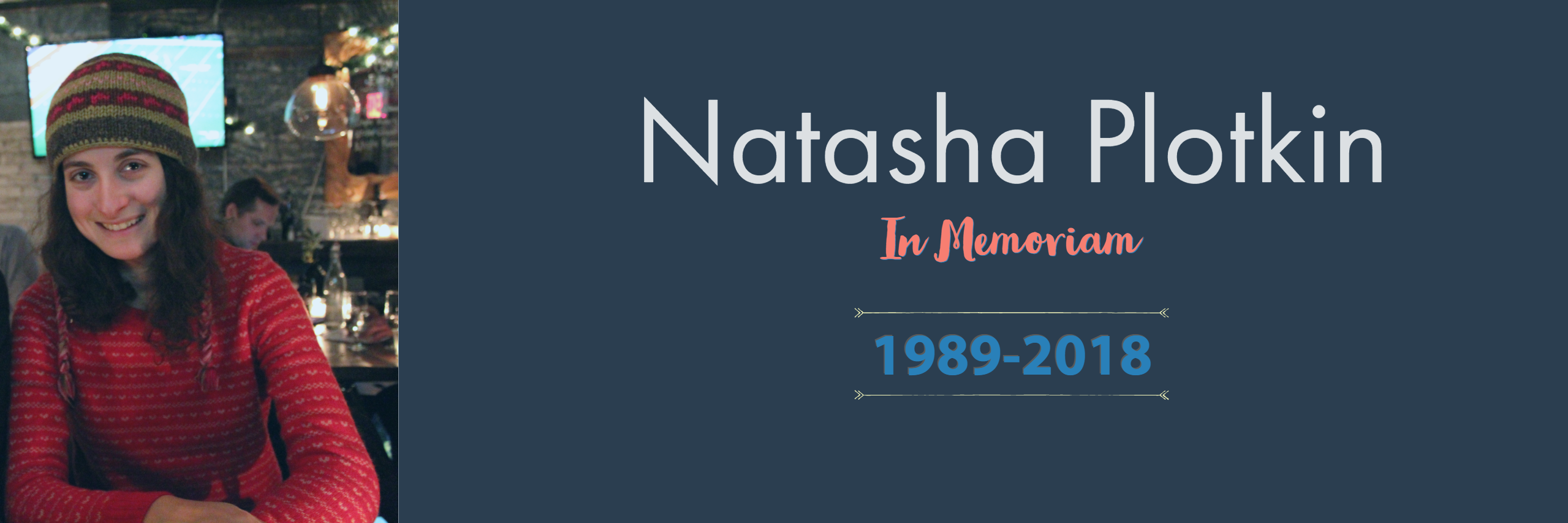

On December 20, 2018, Berkeley Economics Ph.D. student Natasha Plotkin passed away after a long battle with cancer at the age of 29. “Natasha was a valued member of the economics department at Berkeley. We are collectively heartbroken that she was prevented from returning to our community,” wrote Natasha’s classmate, Jonathan Holmes, in an email. “I will personally remember her for her ability to ask insightful questions in class, for her energy and enthusiasm on the Ultimate field, and for the incredibly nerdy jokes we shared. Her wit and insight helped me get through the long hours we spent studying together during our first year. Natasha was committed to using economics as a tool to understand the world and to change it for the better. I miss her perspective, and am deeply saddened that we did not get to see her continue to grow as a teacher and researcher. “

On behalf of the students, faculty, and staff of Berkeley Economics, we share a few words below about Natasha from her colleagues, friends, and family.

Natasha graduated from Hunter College High School, New York, NY, in June 2008. in 2011, Natasha graduated from MIT, Boston, Massachusetts, cum laude in economics. After graduation, Natasha worked at The Brookings Institution, Washington, DC, as a research assistant and editor for Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. From July 2013 to June 2015, she worked for Raymond Fisman, Ph.D., at Columbia Business School, Social Enterprise Program, New York, NY, as a research coordinator, providing data analytics about attitudes toward inequality.

“I like to think her interest in this topic related to her larger interests in life, but I also think she wanted to work on something that had direct impact – which is why I remember talking to her about possibly going to work with/for Give Well,” said Prof. Fisman. “ I count Natasha as a friend. I still remember quite vividly the last time I saw her, for coffee at Joe at 125th and Broadway, after I’d moved to Boston but was back in NY for a visit. She was always so full of energy, wit, and ideas.”

Natasha was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s lymphoma in April 2015. She was treated at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York NY, and was declared officially in remission in October 2016.

In November, Natasha was admitted to Mt. Sinai Hospital for lung complications. Nevertheless, she worked for MIT professor Benjamin Olken, Ph.D., throughout 2017 as a research analyst (formally, as a consultant for the World Bank), analyzing the results of a 9-year study that provided health and education block grants to Indonesian villages. “She was always enthusiastic and eager to take on new and exciting challenges. Her constant ability to analyze the world and her intellect came through in all kinds of different ways," said Prof. Olken. "I was struck when I saw her at Mount Sinai how, in the midst of what was clearly a terrible ordeal, she had all kinds of ideas about the inefficiencies of the healthcare system, and was mulling over how to write a paper about them. “

During the next year, her lungs deteriorated rapidly from the chemo and radiation. She spent the last 14 months of her life at Mt. Sinai Hospital, dying on December 20, 2018.

Natasha’s father, Gary Plotkin, shared below a biographic essay written by Natasha.

My school’s math department changed my life—unintentionally. By erecting bureaucratic walls to my entering the highest math class, it spurred me on to try even harder to a higher-level understanding of math. In the process, I learned about what drives me and became stronger. The saga started in seventh grade.

This year would be my last chance to transfer. I knew everything on the test. The obscure geometry theorems came in handy. I passed the test and entered E math. In the class, I realized I had learned E-math material better than most E-math students had. I soon was earning an A+ even an E-math and, by second semester, I was bored again.

So, although my initial purpose for switching math classes actually was defeated, transferring to E-math had become so much more. While in seventh grade, I thought math wasn’t my thing, I later realized that I had put so much extra time into studying math, I could actually do pretty well. The experience prompted me to start tutoring my friends in math and, at the urgings of my ninth grade math teacher, to join math team. As I became ever more sure that I was capable of doing well in E-math, I found another motivation for switching: I wanted to prove wrong my math department chair and everyone else who had kept me back. I could not let her think her senseless bureaucracy had served me well by keeping me where I was “best placed.” She taught me I could by telling me I can’t.

Cat Pierro and Natasha met in New York in 2014 and became close friends since then. Cat shares her eulogy to Natasha below.

“This death was not exactly unexpected. Not by us, and not by Natasha. Many of you know about her grand attempt to come to terms with what might happen to her, namely, the death reading list. Not only did she read classic texts about death and watch movies about death, but she also had frank discussions with her friends about such death subtopics as

~ how to wrap your head around uncertain odds of survival expressed as a percentage

~ how an awareness of death does and does not lead to greater clarity on how to live life

~ what the meaningful differences are between having some years and having some decades

~ how many kinds of torture the human body could face and how these were so various that they could serve to drive people apart rather than bring them together.

The purpose of all this thinking may have been to be able to face death head-on, but it was never to accept death exactly. The idea of accepting death, of being okay with it, was something she found kind of contemptible — life had so much in store, and to become so beat down and resigned that you *willingly* pass up the opportunity to live that life — that just seemed sad and wrong.

I think part of the reason she was so against dying was the same reason that she hated that chemotherapy robbed her of her fertility. She didn’t want to adopt, she wanted her children to share her unique genetic material. She explained that she believed she had a perspective and a way of being that were special and irreplaceable. I think the reason we’re all here right now is that we agree she did.

Of course, I think I have my own unique perspective on her unique perspective and none of you will ever understand. But seeing everyone’s reactions to her death and hearing everyone’s thoughts and seeing everyone’s Facebook posts has made me think we can get closer to that mutual understanding than I would have thought and it feels good to think that others acknowledged her essence. Like our friend Sruly had a Facebook post that said, “I’m just almost haunted by how casually good she was at engendering the deepest conversations about the most far-flung topics with intellectual grace, dexterity, and overt muscle.” It’s the word “muscle” that got me, because yeah, the verbal tools she had for bringing up awkward topics were plentiful, from “I hope you don’t mind my saying” to “Well now I’m tempted to just ask you a million questions about” to “I don’t see why we shouldn’t acknowledge explicitly that.” Thinking about all these forced yet graceful introductory phrases reminded me of something our friend Aaron said about the things she would write on her whiteboard at the hospital when she was too medicated to be fully coherent. Often the beginning of her sentence would come out great and the end would be illegible, which would be fine if she would just write one-word sentences like “WATER” or “ATIVAN” or “STOP” — but instead they would be like “Do you think it would be possible if you could ask my nurse if she could please” and by that point the sentence would no longer be readable. And Aaron found it really charming that her subconscious was filled with connecting phrases and “if you should so happen to”s.

I know we’ve all really been missing Natasha’s voice. Even composing this speech I’ve been hoping Natasha could just write it for me, as she’s written so many important communications for me in the past four years. So I just want to end by reading some of her words, not any content, just pure voice. These are excerpts from some feedback she gave me on an essay I wrote, and I’ve just isolated some of the phrases that I think honor way of speaking. So here’s Natasha:

"To help me organize my thoughts, I created a list"

"I hope you’ll be able to identify that one, er, okay three, of these items are not like the others. Quick, take a guess about which three they are before you see what I thought!"

"Want a hint?"

"Perhaps you sensed or were even semi-conscious of this"

"I dunno, I may not have a slam-dunk case for this but hear me out here:"

"The key idea seems to be"

"(er, sorry, this isn’t even quite accurately articulated, but I hope you at least kind of see what I’m trying to get at? I think it’s a subtle and therefore tricky-to-express distinction :\)"

"So say you buy my argument"

"Could you spend a little more time thinking about what’s going on there?"

"I intentionally separated this part very cleanly from the rest of my response because"

"At many points in your piece, I found myself thinking, hm, "

"Relatedly, I have a million more questions about"

"Alas, I’m afraid this raises a slightly awkward question about what your aims are in writing"

"The list could go on."

And the list could go on. I wish she could be here to speak for herself, but from now on we’re just going to have to make do with memories.

Comments

Add new comment