Last year, US national income reached its highest level on record: $21.5 trillion. With an adult population of almost 250 million, this amounts to an average income per adult of just over $86,000. This average amount masks vast differences and in recent decades economists have turned their focus to exactly these differences. Berkeley economists Thomas Blanchet, Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman have found that in December of 2021, the average pre-tax income of the top 1% was $1.7 million, while an adult in the bottom 50% earned only $24,000 on average.

With professors Emmanuel Saez, Danny Yagan, and Gabriel Zucman, with the Center for Equitable Growth and the Stone Center on Wealth and Income Inequality, and numerous post-doctoral fellows and PhD students, UC Berkeley has become the epicenter of the global study of inequality.

In my own research, I have worked with a large team of economists in the Netherlands to study inequality there. The Netherlands is one the richest European countries. It is radically different from small-government America in that it combines a large welfare state with high levels of taxation. How effective is such a system in addressing inequality in income and what can it tell us about the challenges faced in the United States? To answer this question, we first start by measuring income inequality before taxes and government spending.

One enormous advantage of doing research in the Netherlands is having access to a wealth of data on the entire Dutch population. Our team of economists and statisticians had access to detailed and anonymized information on individuals’ income earned, taxes paid, and government spending received. This allows us to study inequality and redistribution at a high level of granularity.

We find that inequality in pre-tax income in the Netherlands is substantially lower than that in the United States. Whereas the American top 10% earners account for around 45% of pre-tax income, this is only 31% in the Netherlands, comparable to the levels observed in France and Austria. The bottom of the income distribution has naturally lower levels of income than those at the top, but there’s another important difference. As in other countries around the world, income at the bottom consists mostly of labor income and pension income, while at the top it is predominantly made up of capital income and business profits.

One peculiar finding is that even at the very bottom, households earn a non-negligible amount of investment income through pension funds. Pension entitlements are distributed relatively equitably, which grants even low-income households access to high return investments.

An important feature of our study is that we include all forms of income, including profits retained by businesses. Before assigning these profits to Dutch households, we need to know what fraction of retained profits belong to Dutch shareholders and which fraction to foreign shareholders. This is particularly pressing because the Netherlands is frequently used by multinationals as one link in their elaborate tax optimizing chains. We rely on the Dutch statistics office as well as the central bank that produce statistics on domestic and foreign ownership of firms.

Once we have established the level of inequality in pre-tax income, we can study the impact of government redistribution through taxes and government spending. One of our most remarkable findings is that the Dutch tax system is regressive: the tax burden, expressed as a share of pre-tax income, falls with income. For most income groups, taxes are around 40% of income, but this drops to almost 20% for the top 0.01% of earners.

The Netherlands is not unique in this respect. Professors Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman found that in the U.S., billionaires face a tax burden substantially below that of any other income group. Italian researchers have also documented a similarly regressive tax system. In the Dutch case, there are a number of factors that help explain this pattern. First, capital income and business profits are taxed only lightly. As we mentioned, these are exactly the types of income common at the top. Relatedly, social security contributions are often only levied on labor income, which makes up a small share of income at the top. Finally, the Netherlands levies high taxes on consumption. Because lower incomes consume a higher share of their income, they also pay more in consumption taxes.

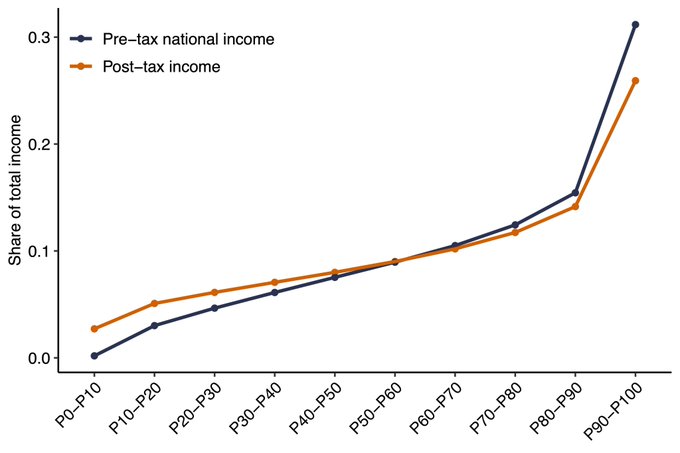

Does this mean that welfare states are unsuccessful in addressing inequality? To answer this question, we must turn our focus to the spending side. We consider all types of spending: collective expenditure, cash transfers as well as in-kind transfers. Here we find that, in contrast to the tax side, spending is progressive and leads to a substantial drop in inequality. The income share of the top 10% falls to 26%, while the bottom 50% increases their share from 21 to 29%. Just to remind us of the contrast with the United States: the posttax income share of the top 10% in the US lies around 36% and the bottom 50% takes home only 22%.

Where does this leave us? The Netherlands has achieved one of the highest levels of development with substantially lower inequality, both pre-tax and post-tax, than that observed in the United States when looking at income shares of the top and bottom. The reduction in inequality is achieved despite a tax system that taxes those at the bottom most, at least in relative terms. This touches on a related research agenda that focuses on the design of taxes. Should taxes be progressive? How does globalization affect states’ ability to raise taxes from the increasingly mobile wealthiest in society? This is a research agenda that should occupy numerous generations of professors and PhD students, myself included.